By now, we’ve all heard about the health benefits of getting enough good-quality sleep. But a new heart health study is taking that age-old advice one step further, suggesting that it’s not just the quantity of your sleep — but when you travel to the Land of Nod — that matters.

In the recent study, people who went to sleep between 10 p.m. and 10:59 p.m. had a lower risk of cardiovascular disease than people whose bedtimes were before 10 p.m. or after 11 p.m. In other words, the best time to sleep may also be what's best for your heart health. The link was especially strong for women, for reasons that require further research.

Read on for the most important takeaways from this new study, plus our sleep advisor’s take on its findings.

Exploring the “golden hour” sleep study

Published in a November 2021 issue of the European Heart Journal-Digital Health, the study tracked the sleep onset and wake-up times of 88,026 U.K. adults over seven days between 2006 and 2010. After researchers collected the sleep data from wrist-worn accelerometers, they followed the participants for an average of 5.7 years to see who would get a new diagnosis of cardiovascular disease — a group of disorders including heart attack, heart failure, chronic ischemic heart disease, stroke, and transient ischemic attack (often called “a mini stroke”).

When searching for patterns between these diagnoses and sleep-onset times, the researchers found that the highest rates for cardiovascular disease occurred among participants who regularly went to sleep at 12 a.m. or later. People who went to sleep during the “golden hour” — between 10 p.m. and 10:59 p.m. — had the lowest cardiovascular disease rates. These patterns persisted even after the researchers accounted for other cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and smoking.

The researchers attribute this effect to disruption of the body’s circadian rhythms (the internal clock that regulates sleep-wake cycles and other bodily functions over a 24-hour period). Circadian rhythm disruptions are an understudied risk factor for cardiovascular disease, the researchers contend, adding that “circadian rhythm disruption is likely strongly related to disrupted sleep timing” at night.

“Our study indicates that the optimum time to go to sleep is at a specific point in the body’s 24-hour cycle and deviations (from that) may be detrimental to health,” noted study co-author David Plans, of the University of Exeter in the U.K.

The link between shift work disorder, which is the disruption of people’s circadian rhythms due to night, early morning, and rotating shift hours, and various long-term health risks may also support this theory. A 2017 study in the Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment & Health found that female nurses who have spent many years working the night shift have a significantly higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease, along with other life-threatening medical conditions.

What sleep experts have to say

While the new study’s findings are intriguing, some sleep experts question the researchers’ conclusions. “Given the way society works, aren't the people (who are) going to bed earlier just sleeping more?” asks Dr. Chris Winter, sleep specialist, Sleep Advisor to Sleep.com, and author of “The Rested Child.” Indeed, the researchers found that the group with the highest rate of cardiovascular disease — those who regularly go to sleep at midnight or later — were sleeping an average of 5.5 hours per night, compared to the 6.5 hours per night among those who fell asleep during the “golden hour.”

Since this new study is a retrospective population study, Winter notes that it’s important to distinguish between correlation and causation. “There is a huge relationship between people who carry lighters and lung cancer. That does not mean carrying a lighter causes lung cancer,” he explains.

“In my opinion, with the size of this population study, they should have normalized all four groups to [get] the same average sleep amount, and then looked at cardiovascular disease rates over time,” Winter adds. Doing so may reveal that, for some, the amount of quality sleep you’re getting has more of a direct effect on heart health than bedtime.

The researchers acknowledge that the findings don’t establish a causal connection between sleep onset time and cardiovascular disease risk. They also identified other important caveats related to their participant population. The cohort was predominantly white and from higher socioeconomic brackets, which poses limitations for generalizing the findings to other populations, the researchers concluded. Just 5% of participants had ever engaged in shift work.

How to tune your sleep to match your circadian rhythm

Despite the study’s limitations, Winter agrees that the regulation of the circulatory system “is extremely circadian.” When circadian rhythms are disrupted, the body’s ability to regulate various aspects of the cardiovascular system is compromised. “It's why stroke, heart attack, hypertension, and heart failure risks are so high in the sleep-deprived and people who are shift-workers or adopters of irregular sleep schedules,” Winter says.

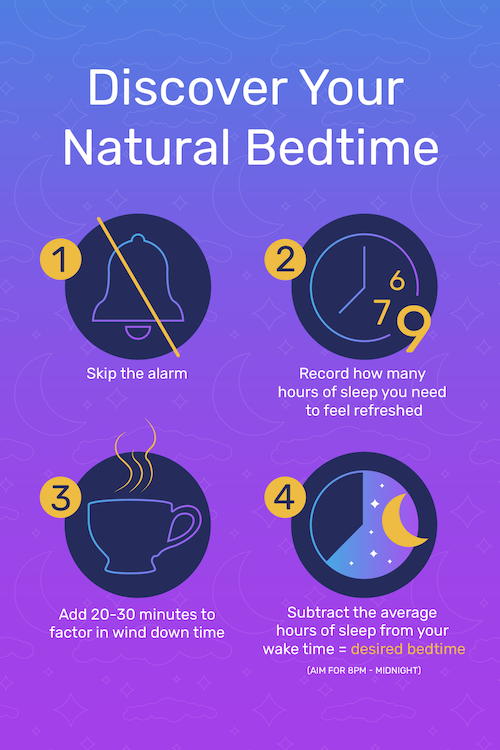

That said, instead of worrying about going to sleep at the “golden hour,” aim to keep a regular bedtime and wake time. Winter recommends carving out a sleep regimen that works for you and sticking with it to maintain consistency. And if you’re wondering what the best wake time is, well it all depends on your morning commitments (work, school, or appointments). Make a note of when you regularly need to wake up, factor in how many hours of sleep you need, and count backwards from there to determine your bedtime.

Setting your schedule may look like opting out of events or setting time limits to activities, especially if it will cut into your sleep. It could also be factoring in a wind down routine as a precursor to your bedtime, so you are more intentional about relaxation and letting your body approach sleep as a process, rather than an on/off button.

Make it a priority and commit to it because your health really does depend on it, Winter adds. As you practice prioritizing sleep to get a regular seven-to-nine hours of shut eye, you’ll see your health and well-being improve in numerous ways. In other words, that age-old advice for good health still lies in getting sufficient sleep.